This story was originally published by San Antonio Report and can be found here.

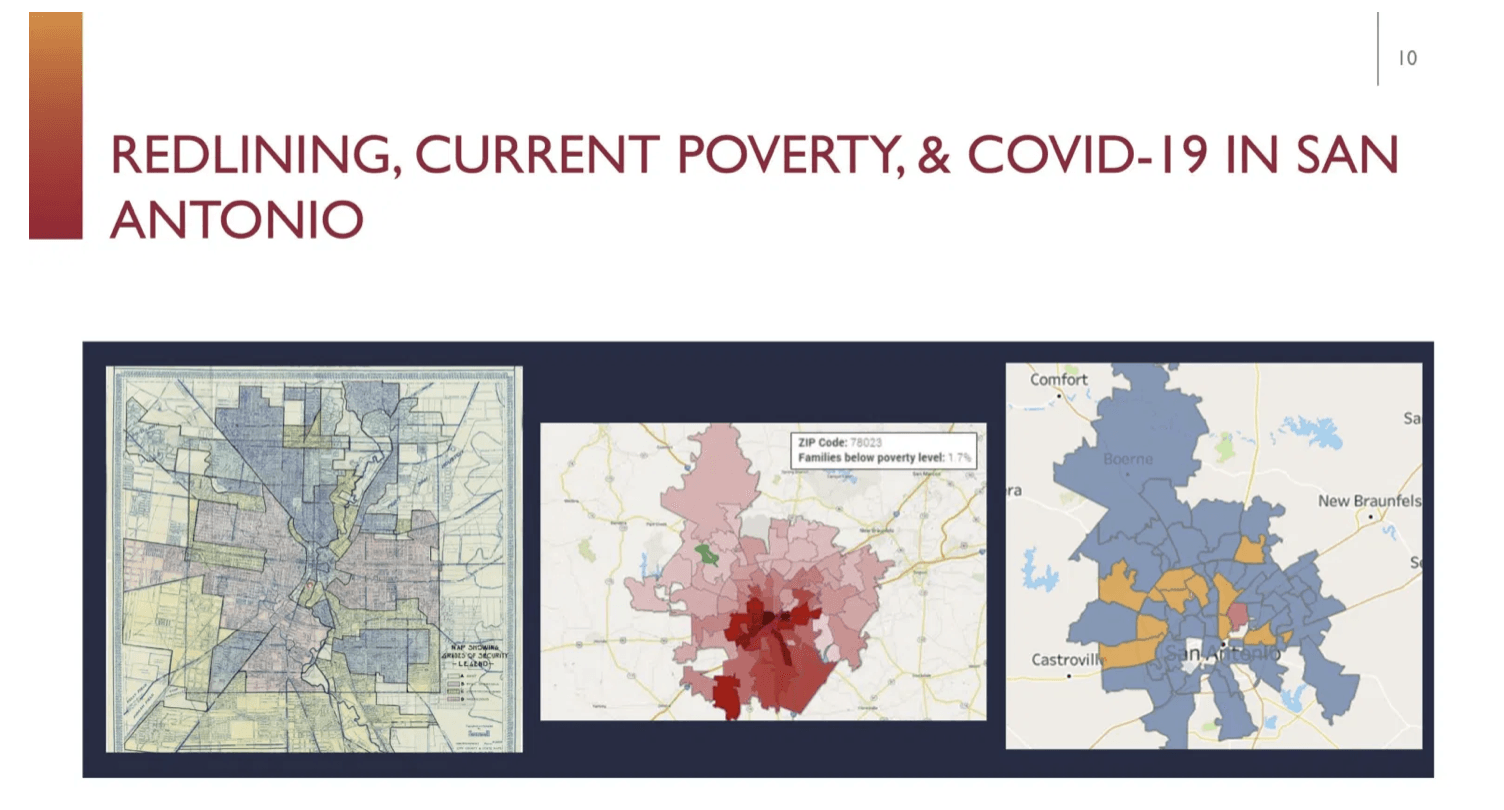

Take a 1930s map of San Antonio’s redlined communities – used to avoid “hazardous” loans in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods – and compare it with a map of families currently living below the poverty level and coronavirus cases. A disturbing pattern emerges: structural racism in action.

Across the country, communities of color have been disproportionally impacted by the coronavirus pandemic in terms of economic and health outcomes, said Dr. Somava Saha, executive lead of Well Being in the Nation Network. “If you look at those places, what you’ll see is that they lack the underlying conditions of [a successful] place,” such as a clean environment, healthy food, and access to health care.

Depending on how communities handle the pandemic, Saha said, “this is either a moment where we are going to erase those red lines or … we’re creating the future redlining maps. … That’s the charge for all of us in this moment in history, is to think about how we use this moment to ‘greenline’ the areas that have been redlined.”

The City of San Antonio’s response and recovery plan is aimed at erasing those lines, said Colleen Bridger, assistant city manager and interim director of Metropolitan Health District. “Literally everything we’re doing is steeped in a focus on equity. … I love calling it greenlining.”

Saha and Bridger spoke during a panel discussion on Friday as part of the San Antonio Report’s five-day urban ideas festival CityFest. They were joined by Erika Gonzalez, president and CEO of South Texas Allergy & Asthma Medical Professionals, and Jaime Wesolowski, president and CEO of Methodist Healthcare Ministries of South Texas, to discuss Saha’s keynote address on health equity and possible paths forward.

Saha, who is a primary care doctor and public health practitioner, likened public health to a fire.

“We [could be] the best-organized bucket brigade trying to put out a fire, [but] there is a tanker full of gasoline going into the fire at the same time,” Saha said.

Similarly, doctors typically address the patient in front of them but not the underlying cause of the illness, she added. “What would it take for us to strategically shift those underlying things in the environment that are driving poor outcomes?”

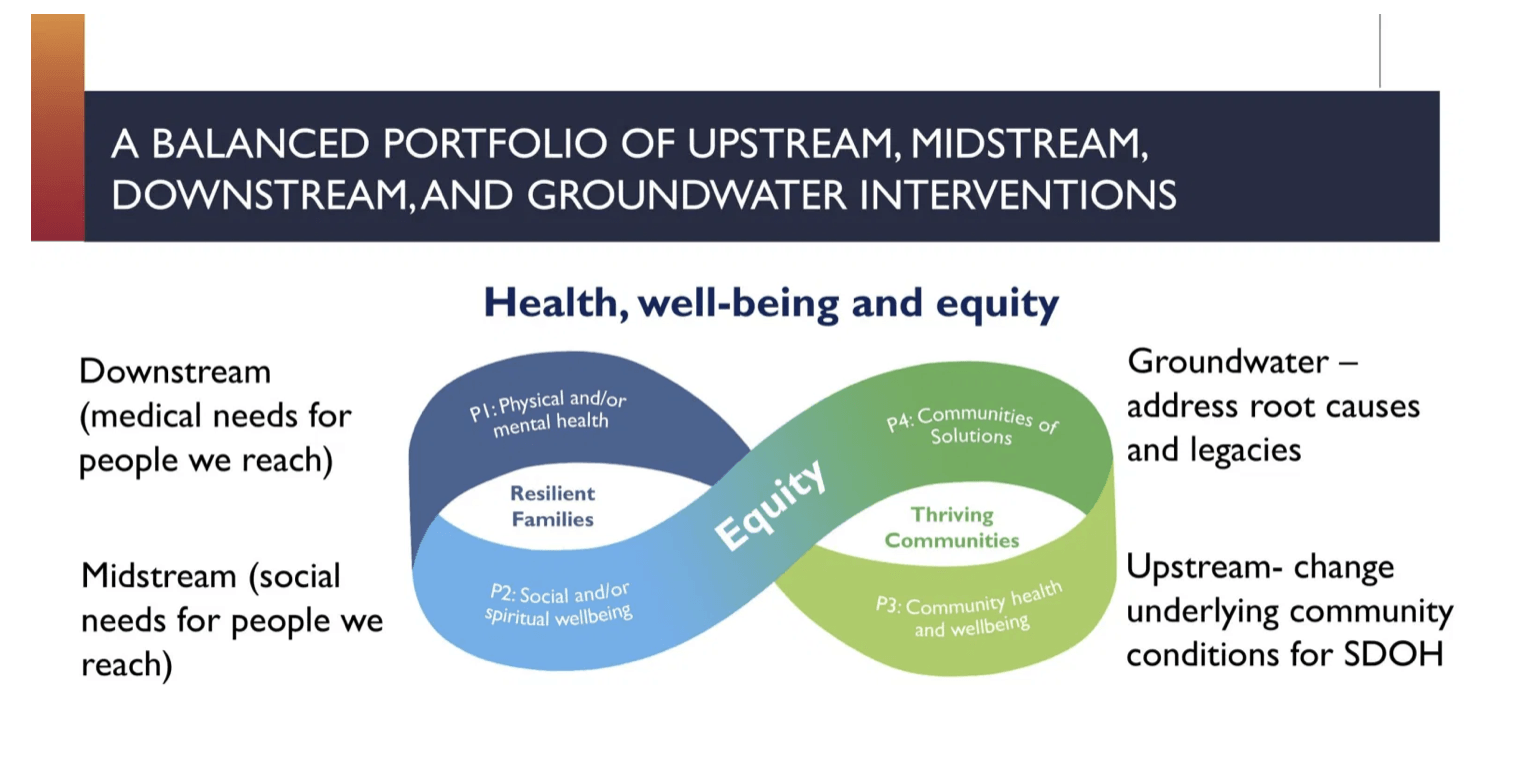

Doctors treat children with asthma with medication – that’s an example of a “downstream” need, she said. But if someone digs further and finds out that their home has dust and mold that is causing the asthma, moving the child to a different home is a “mid-stream” solution.

“If we both remediate [substandard housing] and also create policies that make it possible for those places to [sustain] high-quality housing – and often mixed-income housing – then we begin to change the underlying legacies of disinvestment that got us here,” Saha said. That’s one of the so-called “upstream” solutions.

Saha is working with Methodist Healthcare Ministries to formulate an equity plan for the hospital system to address internal equity and start looking outside its traditional role of treating patients. The hospital system and nonprofit that serves 74 counties in South Texas is looking to broaden its scope to include upstream solutions.

“We need to evaluate not just health outcomes but those upstream social determinants of health … food, housing, education, the list goes on and on,” Wesolowski said. The nonprofit will undergo an internal equity, diversity, and inclusion audit starting next week.

This equity work will involve partnerships with local governments, businesses, nonprofits, and – most importantly – the underserved community, he said.

Door-to-door outreach to low-income communities of color is a priority in the City’s recovery plan, Bridger said, but one of the main barriers is trust.

“Redining happened in the ’30s and here we are today and we’re still seeing those same communities suffering from those same problems,” she said. “They don’t believe us when we say, ‘Oh yes, this time we’re going to help you.’ … The only way to build trust is by saying what you’re doing to do and then doing what you said you were going to do. We’re just now in that transition from the saying to the doing part.”

A key element to building that trust is forming relationships with neighborhood leaders and doctors who are established in those communities, Gonzalez said. Building those networks will help the city roll out its plans to stem the spread of coronavirus and help underserved populations take advantage of workforce development programs and other assistance that is available.

“We’ve often used the Promotoras with our health workers in the community who speak the language, who understand the culture, who look like the people they are trying to help,” she said.

That trust should work both ways, Saha said.

Successful programs that see 50 to 75 percent improvement in health outcomes “are often the ones that are led by or have substantial leadership by those people with lived experience of inequity.”

Health leaders need to trust that the community knows what it needs, she said.

Wesolowski, of Methodist Healthcare Ministries, has learned that an important piece of equity work is listening. “We can’t come in there and tell them what they really need.”