This story was originally published by San Antonio Express News and can be found here.

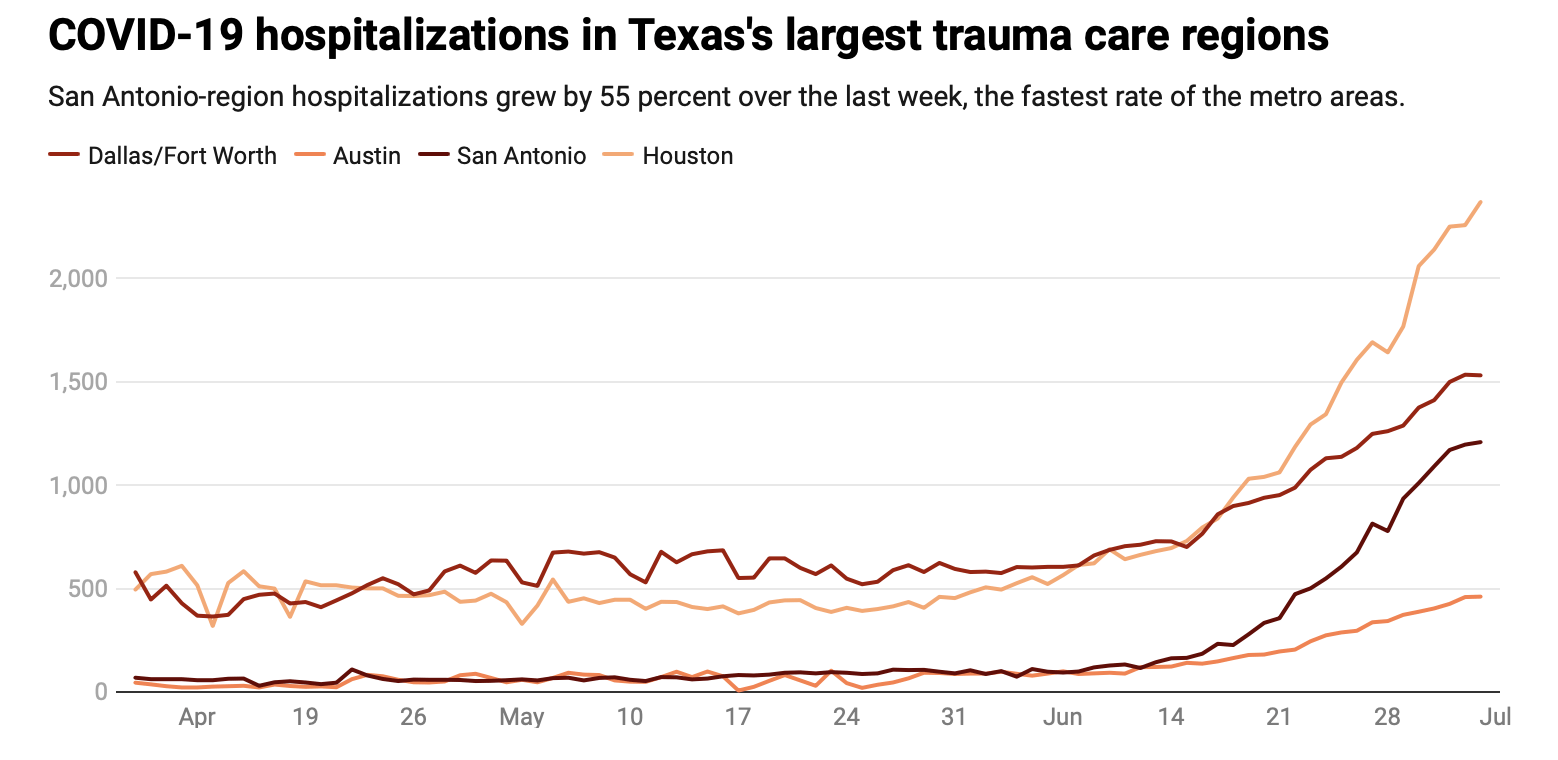

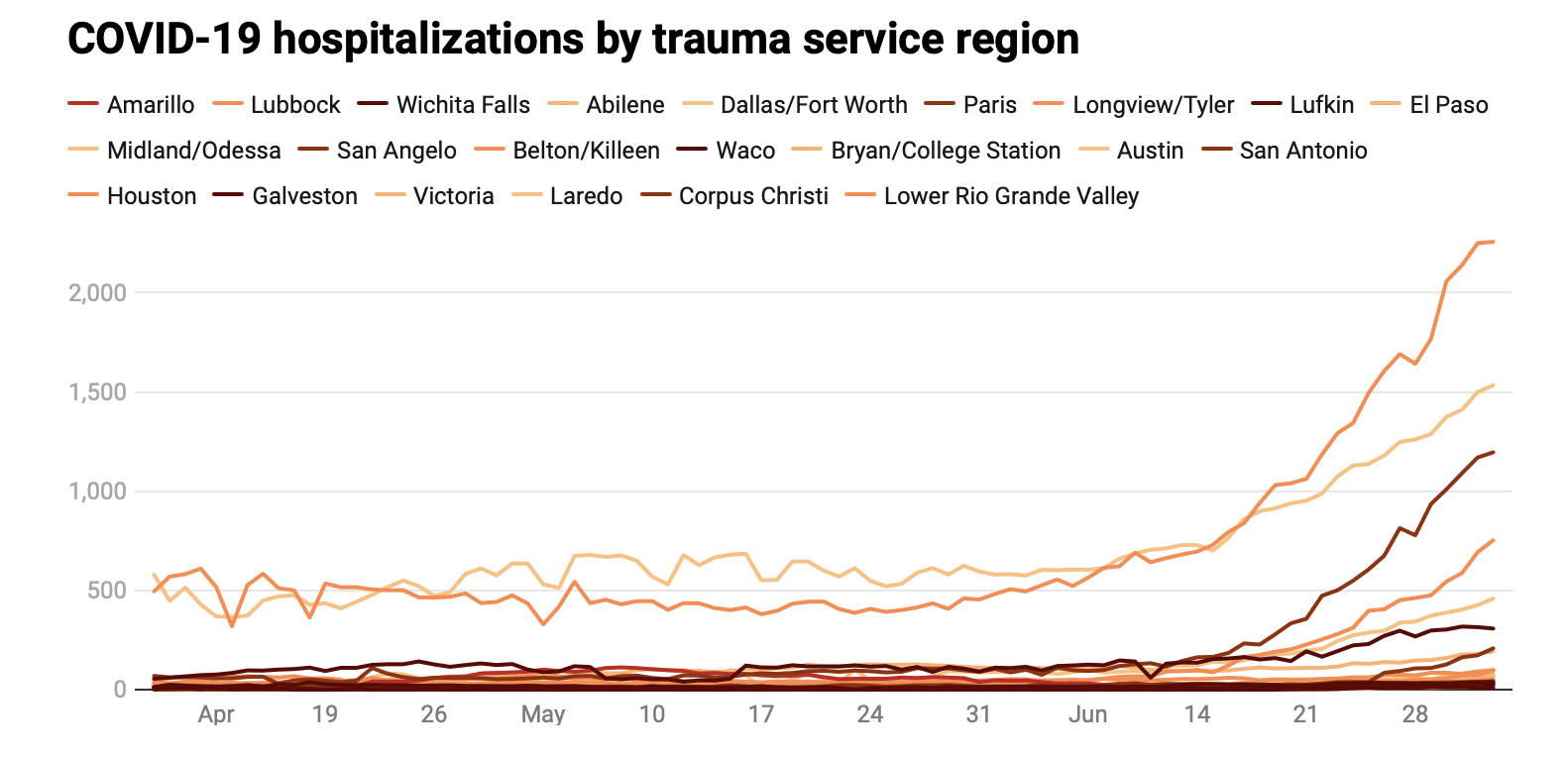

The alarming surge of COVID-19 hospitalizations in San Antonio — where at least one in four new patients has the disease — is growing at a faster rate than in other major Texas cities.

For the last week, the number of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the trauma-care region that includes San Antonio rose by 55 percent, state health department figures show.

If the surge continues, it could overload the local health care system in the next week or two.

The increase in hospitalizations over the past seven days was 44 percent in the Houston region, 34 percent in the Austin region and 21 percent in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. In Houston, the largest medical center in the world exceeded its normal intensive care capacity Wednesday.

Texas has emerged as a hotbed for the coronavirus pandemic, adding more than 43,000 cases in the past week alone. It was one of the states most aggressive about reopening its economy, but Gov. Greg Abbott has been forced to pause further business reopenings, shutter bars and suspend nonemergency surgeries in hard-hit areas to save resources for COVID-19 patients.

Abbott signed an executive order Thursday requiring nearly all Texans to wear masks in public, a reversal of his order earlier in the pandemic that barred local officials from enforcing their own mask mandates.

The state’s major metropolitan areas aren’t the only communities swamped by COVID-19 patients. Cities across South Texas, which rely on San Antonio as a medical hub, are experiencing some of the highest spikes, painting a dire picture of the stress on hospitals.

In the Corpus Christi area, the state reported last week that just nine intensive care beds were available for a dozen counties with a combined population of more than 600,000 people. Hospitalizations there increased by 100 percent over the past week.

In Laredo, the health department director announced Thursday that hospitals had reached maximum capacity. The next day, government leaders said hospitals in the Rio Grande Valley were full, too.

“If we get to that point, where we truly run out of capacity in our hospitals, it means that we won’t be able to care not just for COVID patients, but we won’t be able to care for patients that we care for all the time — that means patients with heart attacks, or strokes or cancer or trauma,” said Dr. Bryan Alsip, vice president of University Hospital in San Antonio. “When we’re full, we’re full.”

For more than two weeks, San Antonio has experienced some of the fastest COVID-19 case growth in the country, ranking fifth in the U.S. and first among large Texas cities.

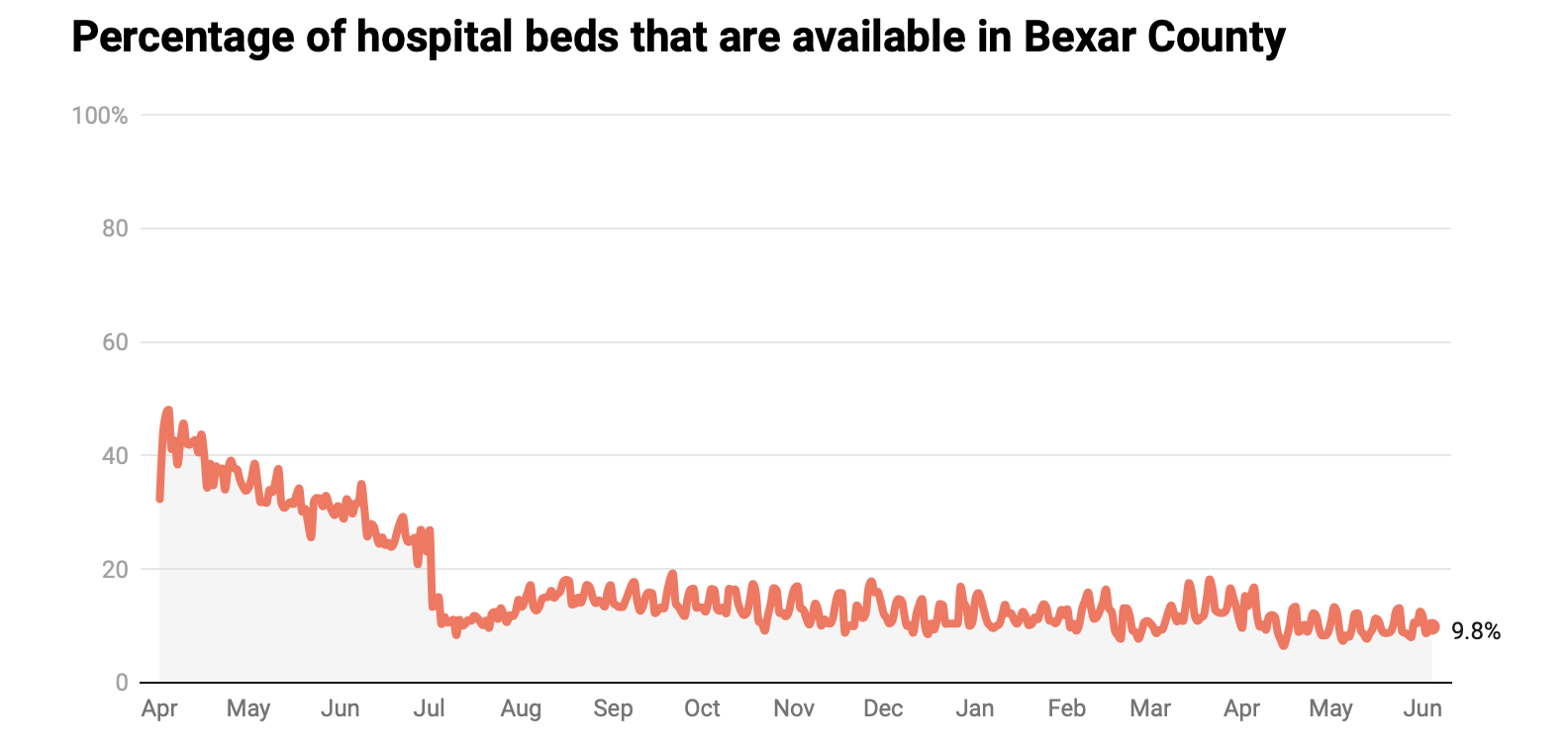

One in 10 people who tested positive for the disease since the start of the pandemic in Bexar County has been hospitalized, the Metropolitan Health District reported.

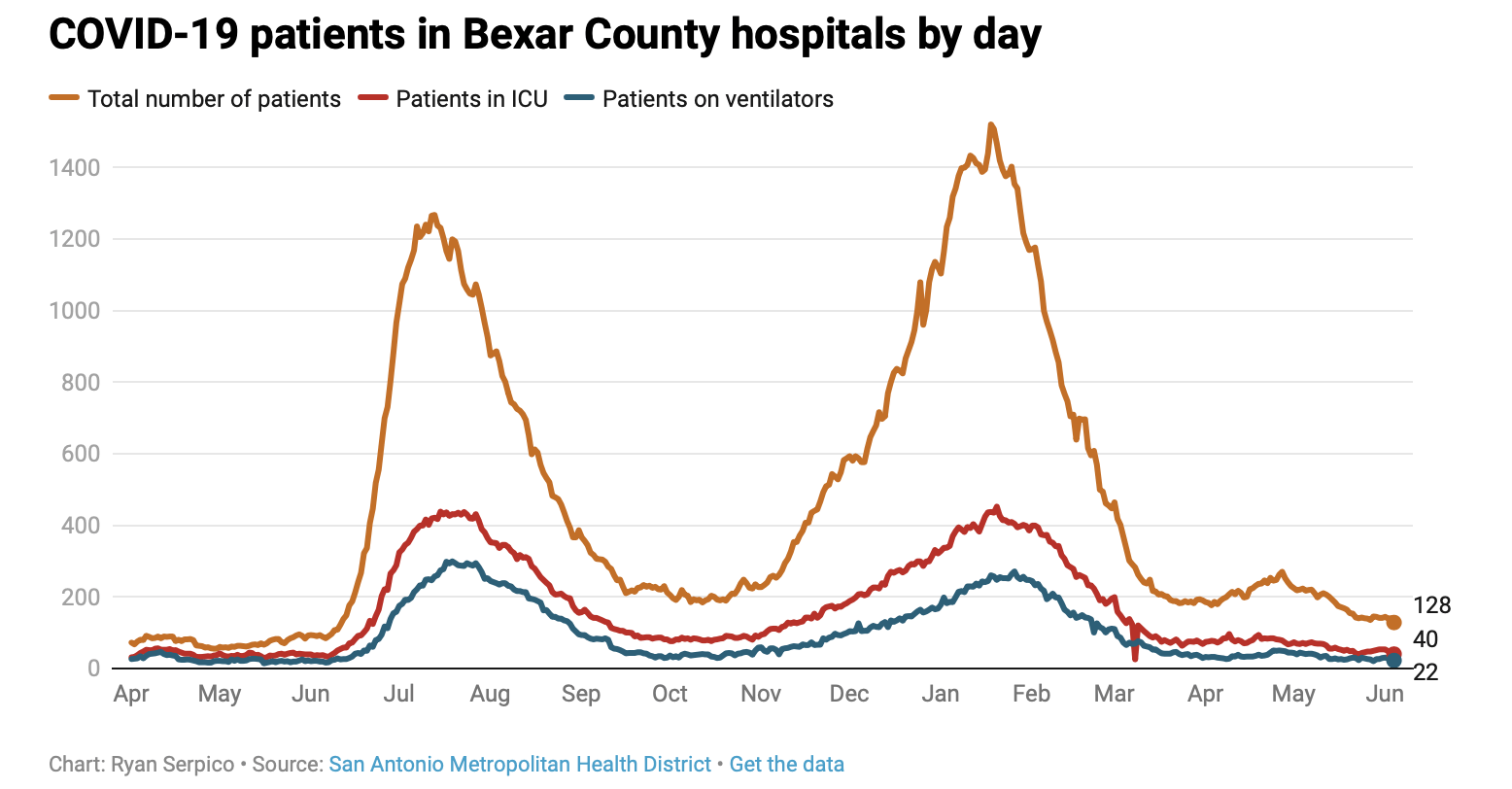

In less than three weeks, the number of patients being treated for COVID-19 in area hospitals has increased more than five-fold — from 176 on June 15 to 1,120 as of Saturday.

There are more COVID-19 patients in San Antonio hospitals now than there are in hospitals in New York, the original epicenter of the pandemic in the United States.

To keep pace with the surge, San Antonio leaders have tapped the state health department and the military to send more than 800 nurses to help staff hospitals. Nearly 180 arrived last week. Seventy more are expected Monday.

Area hospitals are scrambling to add new beds. Recovery rooms normally reserved for surgical patients are being converted into intensive care units. Pediatric intensive care units are being reconfigured to accommodate dozens of adult patients.

Without enough hospital beds or staff, patients could wait hours in emergency rooms before overnight rooms become free.

But hospital leaders say the efforts to rapidly add beds and staff will hit a limit. A disease model developed by Sg2, a health care consulting group, and UT Health San Antonio forecasts 1,800 COVID-19 hospitalizations by mid-July under the best-case scenario.

Initially, that model predicted a worst-case peak of 1,900 hospitalizations in mid-August.

If San Antonians don’t wear masks and continue to spread the disease, the worst-case trajectory now envisions 2,400 hospitalizations around July 21 — more than twice the current patient volume.

“The die is cast probably for the next 11 days. Those folks are infected. They will be coming in,” said Dr. Ian Thompson, CEO of Christus Santa Rosa Hospital-Medical Center. “What you do today will determine what happens two weeks from now — whether you’re in the emergency room with no beds in the inn.”

San Antonio area hospitals had just 647 available staffed beds as of Saturday. The disease model health officials rely on projects that 600 more COVID-19 patients will need hospitalization by next weekend.

Eric Epley, executive director of the Southwest Texas Regional Advisory Council, said hospitals need to create staffed beds “out of thin air” to see San Antonio through the peak. The advisory council, known as STRAC, oversees trauma and emergency care in a 22-county area.

But if the worst-case scenario unfolds and hospitalizations continue to double almost every week, officials will be forced to exercise last-resort options, such as sending patients to specialty hospitals and the 250-bed field hospital at Freeman Coliseum. Eply said San Antonio wasn’t near that point yet.

“The reality is, if you’re in the hospital in the cafeteria in a bed, you still have radiology. You still have respiratory therapy. You still have imaging, lab capability,” Epley said. “You have lots of things that are in the hospital that become much more difficult once you leave the property.”

Catastrophe foretold

Public health experts saw a catastrophe in hospitalizations looming weeks before Metro Health did.

A few days after Memorial Day — and nearly two weeks before then-Metro Health Director Dawn Emerick acknowledged the arrival of a “second wave” of the virus — the Bexar County Medical Society sent a warning to Mayor Ron Nirenberg and Bexar County Judge Nelson Wolff.

“Upon review of local data presented regarding current hospitalizations in the STRAC region due to COVID-19 positive cases, we see a concerning trend developing with an uptick of cases,” said the May 29 letter. “This may be in response to the recent ‘reopening’ of the economy.”

The letter recommended officials keep a close watch on COVID-19 hospitalizations and post a warning indicator on the city website whenever the numbers increase five days in a row.

“They thanked us for the input and passed it along to the appropriate committee,” said Dr. Vince Fonseca, a member of the organization’s board who signed the letter along with two others. “At that time, they were still touting, ‘We flattened the curve, we’re on the downside of the peak,’ and we thought that was incredibly unlikely just by the nature of respiratory pandemics that appear in the spring.”

Fonseca said the society’s concerns largely were dismissed. He believes Metro Health officials were lulled into a false sense of security at a time when they should have been fortifying the city’s defenses, upgrading outdated technology and hiring more case investigators to track the spread of the disease, as recommended by a city-county health transition team.

“We wasted our time,” Fonseca said. “We wasted those weeks. And now we’re scrambling.”

In the weeks that followed, the doctors’ worst fears were realized. Early on in the pandemic, experts had warned that San Antonio, which in 2018 had the highest poverty rate among the nation’s 25 largest metro areas, could be devastated by an uncontrollable outbreak of the virus.

San Antonio for years has been one of the most economically segregated cities in America, where many families live in crowded conditions, with grandparents, parents and young children under one roof.

The poorest residents are more likely to have pre-existing conditions — such as asthma and diabetes — that put them at higher risk if infected with COVID-19. The situation is similar in other South Texas communities, including Corpus Christi, Laredo and cities in the lower Rio Grande Valley, where hospitals are inundated with patients.

Dr. Erika Gonzalez, an allergy and immunology specialist and a board member at CentroMed, a nonprofit health network with clinics throughout Bexar County, said soaring COVID-19 hospitalizations in San Antonio are likely related to the prevalence of underlying medical conditions.

“Asthma rates here in San Antonio, we’re about 400 percent higher than the rest of the state as far as asthma exacerbations and asthma hospitalizations. It’s dramatic,” she said. “It’s not an environmental thing because we all have similar air quality. It’s something more internal, and a lot of it has to do with access to health care, and we’re seeing it mostly in the Latino and African American community.”

Latinos make up about 60 percent of Bexar County’s population but account for about 74 percent of COVID-19 infections. Black residents no longer account for a disproportionate number of cases, but they still account for 15 percent of COVID-19 deaths — even though they are 9 percent of the population, according to Metro Health data.

People of color also are more likely to be infected in part because they are less likely to be able to work from home, Gonzalez said.

“The majority of the essential workers, almost 80 percent of front-line workers at grocery stores, are either African American or Latino,” Gonzalez said. “They are exposing themselves more. That really is a socioeconomic thing. They don’t have the luxury of staying home and sheltering.”

Young infecting old

Over the past few weeks, the average age of patients who require hospitalization has changed. Hospitals have seen a surge of patients under 40. A significant portion have no underlying health conditions that would put them at greater risk from the disease.

Dr. Jan Patterson, a professor of medicine and infectious diseases at UT Health San Antonio, said it appears younger people let their guard down when Texas reopened.

After Memorial Day’s large gatherings, the disease began to spread rapidly. And across the state, mixed messaging on masks from state and federal leaders meant many people didn’t wear face coverings in public or when gathering with relatives and friends.

“These younger people are getting infected, but the thing of it is, San Antonio is really big on family and we have a lot of multigenerational households,” Patterson said. “So even though that parent or grandparent may have not necessarily been out, it’s brought to their household by people who have been out.”

Patterson said more young people are being hospitalized — and when they arrive at the hospital, they often bring with them parents or grandparents who also contracted the disease.

The trend has spurred San Antonio’s health executives and government officials to beg residents to heed warnings — such as avoiding large gatherings, staying 6 feet apart and wearing masks.

Allen Harrison, president and CEO of Methodist Healthcare System, put the danger in starkly personal terms.

“My dad died when I was in college. He never saw me graduate. He never saw me get married. He didn’t meet any of my kids,” Harrison said. “San Antonio is a family-centered city. There are a lot of people who regard their members of their family as precious to them— irreplaceable.

“Why would you gamble those relationships with your family in the midst of a pandemic right now?”