This story was originally published by San Antonio Report and can be found here.

After she found out her children had been denied free state health insurance, Jessica Gutierrez started crunching the numbers.

With a 6-year-old daughter and 4-year-old son in need of regular medication to treat the asthma they’ve both had since they were babies, Gutierrez was faced with a tough choice: buy health coverage through the federal exchange or go with her employer’s plan, even though it would eat up most of her recent raise. Plus, the rent on her Westside house near Woodlawn Lake just went up.

Editor’s Note:

Disconnected is a series about economic segregation in San Antonio.

The series debuts a new story every Monday and looks at economic segregation through the lens of the major beats the Rivard Report covers. The goal was to create a human-centric look at one of the city’s biggest problems.

For more information on why we chose this project or to catch up on any missed stories, visit the Disconnected home page.

“That just means it’s going to put me back to where I’m not bringing home as much as I originally thought I would,” Gutierrez said. “I feel like I take five steps forward and then I have to take three steps back. … But their health is very important for me, and we have these medications every month, and I have to have insurance for them.”

Gutierrez and her kids are among the thousands of San Antonio families dealing with asthma, a complex disease that robs people of breath as their airways constrict and fill with mucus.

Health experts also have said asthmatics are at high risk of serious illness if they contract COVID-19, the disease that has infected nearly 170,000 people around the world, including three San Antonio residents, and caused the death of nearly 7,000 people worldwide. San Antonio officials have not yet confirmed that the virus is spreading from person to person in the community, though many health experts believe that’s only because of a lack of available testing.

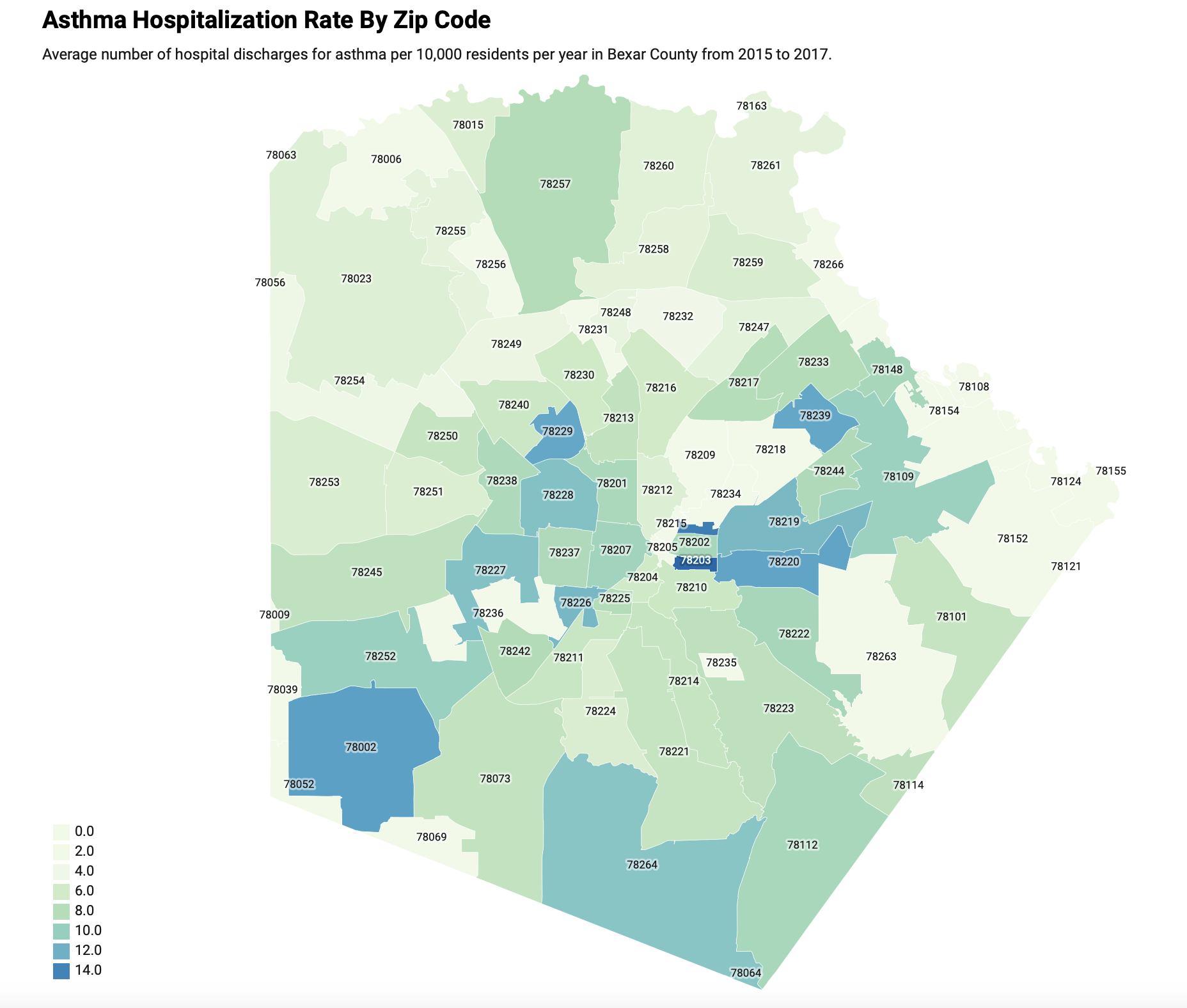

State health records show that San Antonio consistently has the highest asthma rates of any major city in Texas. However, a closer examination makes it clear that asthma does not affect all parts of the city equally.

Zip codes in low-income neighborhoods on the East, West, and Southwest sides had some of the highest rates of people going to the hospital for asthma in San Antonio, according to public health data shared by San Antonio’s Metropolitan Health District.

“We see that areas that have higher poverty levels that are the ones that tend to have the most problems, and a lot of this has to do with access to care,” said Erika Gonzalez, an asthma and allergy doctor who also chairs the San Antonio Hispanic Chamber of Commerce.

From 2015 to 2017, the zip codes with the highest rates of asthma hospital visits were the near Eastside zip codes of 78203 and 78208, where hospitalizations added up to 14 to 15 per 10,000 residents on average over those three years.

That’s around five times higher than the hospitalization rate 2 miles away in 78209, which covers the wealthy enclave of Alamo Heights and the adjacent Broadway neighborhood of Mahncke Park. There, the rate is just over 3 per 10,000 people.

Gutierrez, 33, has spent most of her life in a neighborhood within the 78228 zip code, one of three Westside zip codes where rates averaged around 11 per 10,000.

Asthma has a strong relationship to allergies, and its triggers vary widely. Pollen, air fresheners, smoke, cleaning products, mold spores, smog, pet dander, dust mites, cockroaches, and rodents all can bring on attacks, under certain circumstances.

Aside from the human costs of poor health and premature deaths, asthma also can drag down a region’s economy when it leads to days of missed work and school. Researchers with the American Thoracic Institute and New York University have estimated that San Antonio’s ozone pollution alone is responsible for nearly 107,000 instances in 2019 when a person had to miss work or school because of a lung condition

“There is a financial burden of asthma on the government and on residents,” said Haley Feazel-Orr, an epidemiologist at the San Antonio Metropolitan Health District. “It takes up taxpayer dollars and insurance money, and [it affects] hospitals when someone can’t pay for their hospital bills because they had to go the emergency room because they were having an acute attack.”

Finding Asthma Triggers

Health researchers have noted that asthma tends to run in families, though its genetic influences are complicated. Gutierrez and her brother both developed asthma as children. As an adult, she still experiences the coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath that characterizes the disease.

Doctors diagnosed both of her kids by the time they were a year old, Gutierrez said. She recalls when she used to lug around the machine used to administer albuterol, the bronchodilator medication that helped open their tiny airways when they suffered attacks.

It took a visit to an allergist around a year and a half ago to find out what triggered their attacks, she said. They each got an allergy test, conducted with a series of pinpricks to see if their skin reacted to certain allergic triggers. Gutierrez found out that she’s mostly allergic to mountain cedar. For her son, it’s mold spores. Her daughter suffers from grass allergies.

Once Gutierrez knew this, she could plan ahead for allergy seasons. Plus, she found a doctor who would answer her phone calls, offering advice that could keep the family out of urgent care clinics.

“We’ve been under control for about a year and a half already,” she said. “It’s been a while since we’ve had to go in [to urgent care].”

Lately, however, there’s been the question of insurance.

That became an issue only after her recent raise, when she took a new job as an administrative coordinator at the nonprofit SA2020. It boosted her income to a level at which her kids no longer qualified for the Texas Children’s Health Plan, she said. She thinks she’ll go with her employer’s insurance plan, even though the extra money she’ll pay in premiums will eat up all of the extra money she’s bringing in.

Overall, asthma is still a factor in Gutierrez’s life, but not a barrier. After earning her associate degree in business administration, she expects to get her bachelor’s degree in the same field in the next couple of years. She’s also spoken to a mortgage lender who says she can get on the right track to eventually borrow enough to buy her own house. All of this has been easier with their asthma under control, she said.

“Right now, we’re in a really good spot compared to where we were three years ago,” she said.

Oak Pollen and Air Fresheners

San Antonio is home to several programs focused on helping people like Gutierrez learn how to manage asthma on a daily basis.

For example, the City’s SA Kids BREATHE program sends community health workers, also known as promotoras, into residents’ homes, teaching people how to find their asthma triggers and use medication properly. From May through November, the program had more than 80 participants.

“We’ve had positive outcomes, for sure,” said Paul Kloppe, a respiratory therapist who oversees and mentors the team of health workers who visit participants’ homes three to five times over a six-month period.

However, there’s been much less local interest in tackling one of the broader issues associated with asthma: poor air quality.

Federal regulators consider San Antonio’s air quality to be officially unhealthy because of ozone, a pollutant tied to vehicle exhausts, industrial sites, and chemical use, among other sources. In Bexar County, nearly 60 percent of emissions of the nitrogen oxides that help form ozone come from mobile sources, such as vehicles and construction equipment, according to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ).

Despite this, the TCEQ this year produced a study focusing on the relatively small amount of ozone wafting in from foreign countries as part of an argument to federal authorities to avoid more stringent air quality regulations in San Antonio.

At a February TCEQ hearing, Alamo Area Council of Governments (AACOG) Executive Director Diane Rath, San Antonio Chamber of Commerce CEO Richard Perez, and Bexar County Commissioner Kevin Wolff (Pct. 3) all praised the study. Each emphasized the negative effect that more stringent air quality rules could have on the local economy.

During the hearing, which lasted less than an hour, Terry Burns, a retired doctor who chairs the Alamo Group of the Sierra Club, was the only speaker to mention public health.

“As a physician, I think that should be remembered that … the purpose of this activity we’re all engaged in [is] to protect people’s health,” Burns said. “I call upon San Antonio and the AACOG to actually get busy and take action to reduce our local ozone production.”

Some asthma triggers are beyond anyone’s ability to control. Some of the worst times for asthmatics are during the dreaded Ashe juniper season, December through February. Oak pollen and mold spores also spike at different times of the year.

Others factors are up to individual choices, such keeping a clean home, not smoking, and avoiding fragrant products. These factors are often the focus of Diane Rhodes, an asthma educator with North East Independent School District who in early March taught a free class for parents.

“Asthma doesn’t happen overnight,” Rhodes explained to her lone attendee, a mother of five children. “It happens over a period of days.”

Rhodes explained how allergic and other triggers stack up until a person reaches a “symptom threshold” and suffers an asthma attack. An asthmatic might be OK during a smoggy day in the middle of oak pollen season until they enter a room with too many air fresheners. Identifying triggers is the way to get to a normal life with as little medication as possible, she said.

That’s how the fight against asthma in San Antonio continues – family by family and home by home.

“We have the time to meet families, to get to know families,” said Tracy Compean, a community health worker with SA Kids BREATHE.

‘Just Keep Moving Forward’

Recently, Compean and Kloppe have been visiting Monica Casillas at the mobile home park in south Bexar County where she lives with her husband, Miguel, and their 8-year-old son, also named Miguel.

A former elementary school teacher, Monica Casillas met her husband in 2007 at a family barbecue. They fell in love, and she ended up leaving teaching to raise their son. Now, young Miguel has severe health problems, including asthma and diabetes. An asthma attack landed her son in the hospital in November, she said.

“He turns red and can’t stop coughing,” she said.

For a long time, her husband made a living doing landscaping and construction work, despite having high blood pressure and diabetes, she said.

But starting last April, he suffered a series of four strokes and has not been able to work since. The family could end up waiting until next year to hear whether her husband qualifies for health insurance through Medicare, which is available for certain people under 65 with disabilities. For now, the family is uninsured, and their medical bills are stacking up, Casillas said.

Free programs are helping fill some of the gaps. Casillas found out about SA Kids BREATHE through a City social worker who also helped her son get enrolled in a homeschool curriculum through his district. Compean has been able to find them free food and clothing through local charities and government programs.

“San Antonio has a lot of resources,” Compean said during an interview last week at the Casillas home. “I have a lot of connections I can call upon.”

However, those resources can be intermittent, with funding and other support sometimes running out, Compean said. Coordinating her family’s care is also a full-time job for Casillas, who said she spends hours on the phone talking to health providers, social workers, and others who might help. That’s in addition to her efforts to make sure her son and husband get the daily monitoring and medication they need.

Still, Casillas said the asthma issues have been better since getting her son on the right medications. Sometimes, however, the challenges can seem overwhelming.

“Just keep moving forward, and have patience,” Casillas said. “That’s all you can do.”